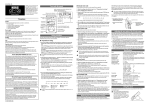

Download The Verituner 100 User Guide

Transcript